Yankton College no longer exists. But it’s not fully dead either.

But the college Garrity runs—in the once-booming, now-sleepy Missouri River town of Yankton, South Dakota—is different than most postsecondary institutions in that it doesn’t do any of those things. That’s because the school—the Dakota Territory’s first college—closed down in December 1984, following decades of financial instability compounded by a decline in enrollment.

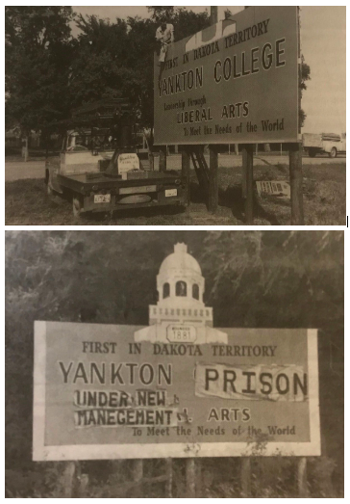

The U.S. Bureau of Prisons ended up buying the college’s property a few years after the closure, and the onetime campus—with its astronomical observatory and garden-terrace theater, its buildings bearing the names of school leaders and donors, and a dining hall that once served imported-oyster dinners—has housed a federal prison ever since. Khaki-uniformed inmates now spend their days barricaded from the outside world in the same corridors and lecture halls and dorms that once served as bridges to that very world.

So why employ an executive director to oversee a college whose only tangible remains serve not to enlighten but to incarcerate? Why even refer to Yankton as a college, when it stopped functioning as one three decades ago?

Yankton College continued (and continues) to exist even after it tied up the loose ends, too, and this is where Garrity comes in. Part of her job resembles that of a registrar: There are transcripts and other student records to maintain and provide to alumni if and when they request copies, for example. Alumni-relations duties account for another chunk, such as the all-class reunions, popular events that draw roughly 200 alumni from around the country to Yankton every two years and supplement the regional alumni get-togethers in areas ranging from New England to Arizona. (The agenda for the biennial reunions always includes a tour of the prison.)

There are also funds to be raised from those alumni, of course—as well as funds to be spent. Garrity’s days as of late have mostly revolved around the spending side of things—namely, efforts to preserve the college so that it doesn’t fade into obsolescence once its last alumni (the youngest of whom are now in their 50s) die. Without Garrity, who would ensure that the alumni-supported scholarships Yankton awards annually to college students are funded in perpetuity? Most important, who would maintain the college’s history and artifacts? Garrity’s latest endeavor has focused on mapping out the school’s forthcoming Alumni and Educational Center, located in a local history museum and slated to open next year. The long-awaited center—which will include exhibits and resource rooms—will, according to the college’s website, serve as “space of our own where we can gather and commune amongst those who have gone before us—faculty, administrators, groundskeepers, actors, philosophers, athletes, musicians, and so many more.”

Yankton’s closure “was devastating. The community was crushed,” says Garrity, who didn’t attend the college but whose family is from the town of Yankton. “It didn’t matter if you were an alum or just a business person—it felt like a huge loss, both historically and economically.” Garrity says she has a passion for the college by way of osmosis; now she’s “a fixed part of its family.”

More than 1,200 higher-education institutions have closed in the past few years due to inauspicious economic circumstances eerily evocative of the context in which Yankton found itself back in the ‘80s. Like Yankton, many of them were small private liberal-arts colleges whose limited endowments rendered them heavily dependent on student-tuition revenue; and like Yankton, some were too tightly tethered to an outmoded understanding of higher education or a religious mission that made innovation difficult or unappealing.

Read: The surreal end of an American college

A shuttered college then likely needs to liquidate its assets, including its land and everything on top of it, from the buildings to the bookshelves. This process can at times be relatively seamless: Education companies based in China, for example, have bought a number of recently closed campuses across the East Coast with the intention of revitalizing them as K–12 schools or new higher-education institutions. But the process can easily propel a soon-to-be-closed college into a protracted, or circuitous, demise, particularly if zoning laws restrict the kinds of activities or occupants permitted on the given land, Joe D’Angelo, who runs the higher-education group at the investment bank Carl Marks Advisors, told me.

A college may buckle under the financial pressures, selling its land to anyone who meets the zoning criteria and is willing to pay the asking price—even if the buyer’s plans for the property deviate from the closing institution’s core objectives, or are a source of community tension, as was the case when Yankton became a prison. In fact, Yankton’s predicament—and the unusual outcome—wasn’t unique: Around the same time in the mid-1980s, another small South Dakota college abutting the Missouri River was met with a nearly identical fate, reluctantly shutting down and selling its land to the state, which converted the school into a prison. Years later, the prison’s inmates reportedly helped construct a room to house the college’s museum.

Real-estate negotiations take time even when the hiccups are few and the demand is high—time that a closing college can’t afford to waste. So, in an effort to eke out as much capital as possible, as quickly as possible, a college may hold a closeout sale while the campus sits on the market, getting rid of all the equipment and supplies and memorabilia that once made the school a school. A recent example is Newbury College, a Boston-area school that shut down in May. A month after shutting down, the institution—whose $40 million campus has yet to secure a new owner—contracted with a liquidator that has started to partner with colleges amid the uptick in campus closures, despite its traditional clients including bankrupt companies such as Toys “R” Us and Circuit City.

As a growing number of higher-education institutions find themselves on the brink of a shutdown, however, administrators are getting savvier and more deliberate about schools’ postmortem existences. Detroit’s Marygrove College, for example, recently announced that it would be closing after the upcoming fall semester, citing its inability to overcome financial troubles. But the college, which these days offers only graduate degrees and is primarily focused on teacher training, started preparing for its end three years ago, when its leaders solicited the help of the Kresge Foundation, a national philanthropic organization, and began hacking out contingency plans that they felt would uphold the school’s values in the event of a major disruption.

This plan, Jackson suggests, not only guarantees that the campus continues to promote the school’s commitment to equity in education, but also tests out a model that could provide valuable insight into the kinds of settings that best promote student achievement and offset socioeconomic disparities. Helping steer the entire initiative is the Marygrove Conservancy, a nonprofit comprised of leaders from Marygrove, Kresge, and partner organizations that the college set up early on in the transition process. The entity will be tasked with helping to manage the transformation and stewarding the school’s 53-acre campus to ensure that its new residents hold to this vision after the college is dissolved.

From Yankton to Marygrove, the takeaway is consistent: A college lasts forever. Or, if not forever, at least well past its date of closure.

For more details check out The Atlantic news